Making the Connection: Incorporating Shared Micromobility Into Multi-Modal Transportation Networks

For many of us, our commute to work for the last two years has simply been to walk from one room to another. However, getting to work or other services looked very different before the pandemic. The pandemic has helped highlight the shortcomings of a transportation system designed to move cars and not people. As we shift back to “normal” daily life, we have an opportunity to reimagine the transportation ecosystem.

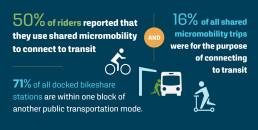

When NABSA pictures the ideal transportation network, we see multi-modal systems that provide options to accommodate a variety of users. A crucial aspect of that system is the inclusion of shared micromobility. As a flexible transportation option with comparatively low overhead and operations costs, shared micromobility is a beneficial complement to transit services. According to the 2020 Shared Micromobility State of the Industry Report for North America, 50% of riders used shared micromobility to connect with transit, and 16% of the 83.4 million shared micromobility trips taken in 2020 were for connecting to public transit.

The recent launching of new multi-modal programs suggests that these numbers will only increase as networks become more integrated and when mobility infrastructure is strategically planned to serve all modes. For example, this May, the Regional Transportation Commission of Southern Nevada (RTC), which manages both bikeshare and transit, collaborated with BCycle and Bicycle Transit Systems to fully integrate both modes within the Transit app. As a result, Las Vegas riders can now purchase transit and bikeshare passes with a single Transit app account. Additionally, MoGo, Detroit’s bikeshare system, is working with the Detroit Department of Transportation and SMART, Southeast Michigan’s regional public transportation provider, to integrate its bikeshare system with transit to promote a more equitable transportation ecosystem in Detroit. In 2020, Austin’s Capital Metro integrated Austin BCycle into its transit system and rebranded it as MetroBike. There are similar initiatives in Los Angeles and Kansas City.

“You can’t understate the importance of connecting communities to jobs and services via not only transit, which is crucial but also by bridging the gaps in the first-last mile connections to transit,” said Benito Pérez, policy director at Transportation for America. “Shared micromobility, where deployed, has and can be pivotal to not only enhancing transit but also improving affordable community mobility to jobs and services.”

Not only do multi-modal networks help cities to meet their equity goals, but these networks can also help meet climate goals. For example, the 2020 State of the Industry Report found that 36% of the trips taken that year replaced a car trip resulting in an offset of approximately 29 million pounds of carbon emissions. In addition, a new study from the International Transport Workers’ Federation and C40 showed that city residents worldwide need to choose modes like walking, biking, and transit for at least 40% of the miles they travel by 2030 to prevent global heating from exceeding the 1.5° Celsius threshold and mitigate the worst impacts from global warming.

Shared micromobility is a powerful tool that cities and transportation agencies can leverage to provide robust transportation networks that meet climate, equity, and access goals, and more investment and collaboration are needed.

“Cities need to think bigger about what is preventing people from using micromobility for multi-modal trips – is it too expensive, too confusing, too dangerous? – and start working with shared micromobility operators to address those barriers,” said Dana Yanocha, research manager at ITDP.

An example of a new kind of collaboration thinking outside the box is in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Move PGH is a two-year program — the first in the nation — to connect different mobility services all over Pittsburgh. The services available include Spin, Port Authority, Healthy Ride, Scoobi, Zipcar, and Waze Carpool. These modes can all be booked and paid for through a single digital platform provided by Transit App. To balance the digital aspects of the program with the physical, mobility hubs were incorporated to provide a place to access a diversity of services reliably. Most hubs are located near frequent transit stops and Healthy Ride stations. The hubs also offer electric charging for e-scooters and real-time transit arrival information via dynamic TransitScreens. In addition, several hubs provide additional amenities, including nearby Zipcar carshare rentals, Scoobi moped parking, and more.

Digital integrations, like that utilized by Move PGH, are made possible through sharing real-time system information. The General Bikeshare Feed Specification (GBFS) is a standard format used to share the real-time status of shared mobility systems. It helps cities, transit agencies, and mobility providers to build shared micromobility into trip planning platforms and provides users with the ability to locate vehicles.

Another contributing factor impacting the development of multi-modal networks is transportation and infrastructure policy. Provisions that passed through the recent Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) in the US, like increased funding for the Transportation Alternatives Program (TAP), and shared micromobility’s eligibility in the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program (CMAQ) and the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program (STBG), have resulted in new and increased access to capital funding for shared micromobility and the infrastructure that supports it. TAP is the largest source for safe street infrastructure, while CMAQ and STBG provide shared micromobility projects with access to federal funding that can support related infrastructure, the launching of new systems, and the expansion of existing systems. Much of this comes as climate and smart mobility are being prioritized globally. For example, 25 mega-cities, including Rio de Janeiro, New York, Paris, Oslo, and Mexico City, have pledged to be carbon neutral by 2050. Additionally, President Biden signed an executive order that aims to have the US federal government carbon neutral by 2050.

“A colleague once pointed out that car infrastructure takes up a lot of space visually. When you step out of your front door, the road is right there. You see highways, and they’re huge,” said Benjie de la Peña of the Shared-Use Mobility Center. “Infrastructure for shared micromobility may be on some roads, and maybe it’s a protected lane. If people see safe, shared micromobility infrastructure everywhere, like they see car infrastructure, they may be more likely to replace car trips with micromobility.”

Communities are diverse and need transportation systems with options as diverse as they are. Integrating shared micromobility into these networks helps travelers complete an entire trip by providing first and last-mile solutions, filling transit deserts, and providing important redundancy to transit services that we have especially seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. Multi-modal networks also increase efficiency while lowering car dependency, providing equitable access to transportation, and helping reduce the carbon footprint of transportation. Integrating shared micromobility into multi-modal transportation networks is necessary to achieve these goals.

Learn more about shared micromobility’s transportation impact in the 2020 Shared Micromobility State of the Industry Report for North America.